This post will deal with Pre-Raphaelite interpretations and depictions of Death in art.

Ophelia 1851-2 John Everett Millais

Millais' Ophelia is probably the most famous of all Pre-Raphaelite paintings that deals with death. The painting shows the point, from Shakespeare's Hamlet, where Ophelia goes mad when her lover, Hamlet, murders her father, and she drowns herself in a stream. The flowers in the stream all have significance (of which the Victorian public would have been familiar) - for example poppies signify eternal sleep; death, and violets for faithfulness, chastity or death of the young,

The Death of Chatterton 1856 Henry Wallis

Wallis' painting depicts the death of Thomas Chatterton, a young romantic poet/forger of medieval poetry. Chatterton died of arsenic poisoning at the age of 17; either a suicide attempt or an attempt to medicate a venereal disease. Chatterton was praised and considered a Romantic hero by many of the Pre-Raphaelites of that time; idolised and commemorated by Rossetti in his 'Five English poets', and by Wallis in this painting. Shelley, Keats, Wordsworth and Coleridge also wrote poems about the young poet; Keats inscribed Endymion 'to the memory of Thomas Chatterton'. Wallis, in keeping with Pre-Raphaelite ideals, used vibrant colours and realistic and symbolic details - the brightness of the poets breeches and jacket signifies his youth and genius, and the fallen rose petals and guttering candle symbolise a life cut short. The place in which Wallis painted this scene was in fact very near to where Chatterton died, though it is uncertain whether he knew that. Wallis used the young George Meredith for the figure of Chatterton.

Oh What's That in the Hollow? 1895 Edward Robert Hughes

This painting is rather unusual for Hughes, whose other works are nowhere near as dark as this. However, it is very much inkeeping with Huges' style of painting. The roses that surround the corpse look reminiscent of Edward Burne-Jone's series of paintings The Legend of Briar Rose, completed a few years earlier. In this painting, Hughes has chosen to depict the fourth stanza from Christina Rossetti's poem Amor Mundi, in which two lovers encounter foreboding omens and dead bodies while walking together:

“Oh what is that glides quickly where velvet flowers grow thickly,

Their scent comes rich and sickly?”—“A scaled and hooded worm.”

“Oh what’s that in the hollow, so pale I quake to follow?”

“Oh that’s a thin dead body which waits the eternal term.”

The Stonebreaker 1857 Henry Wallis

This painting by Wallis at first depicts a stone-breaker resting after a hard day's work. It is only after closer inspection that the viewer begins to sense something more sinister. The hammer has slipped out of the mans hand, not placed, and he lies in an unnatural position. The twilight and autumn season signify the ending of life. When I went to see this painting at the Tate, it was only from studying it in reality that I realized that the man was dead; if you look closely there is a little stoat approaching the man's foot, which would not come that close if the stonebreaker was anything other than dead. Wallis is thought to have painted The Stonebreaker as a response to the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act, which formalised the workhouse system as a way of regulating the poor, and discouraged other forms of relief. Given the context of this, Wallis can be seen to be commenting on the treatment of the poor at the time in England, especially the way that government dealt with the problem. On a more jolly note; the sunset is stunning.

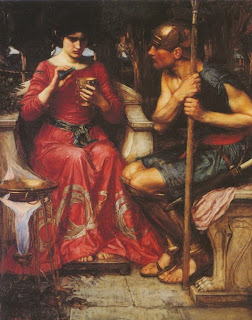

Hypnos and Thanatos: Sleep and His Half-Brother Death 1874 John William Waterhouse

This painting by Waterhouse depicts the Ancient Greek personifications of Sleep and Death. Sleep, Hyponos, can be identified as the first brother with poppies in his hand - a symbol of sleep. Thanatos was the Ancient Greek personification of Death; a minor God who, though often referred to, rarely appeared in person. Thanatos was often shown as a cruel and heartless god, so it is unusual how Waterhouse chooses to depict him as a harmless looking youth. Interestingly, though, in Ancient Greek times Thanatos was mostly shown as a winged man, but as death became though less of a horrible demise and more of a gentle passing and part of life, Thanatos began to be depicted as a youth or even cherub; differing from Cupid by crossed legs and an upside-down torch - signifying life extinguished.

Death Crowning Innocence 1886-7 George Frederic Watts

Watts' Death Crowning Innocence is an unusual depiction of death. As with most of Watts' works the meaning is rather elusive and ambiguous. An interesting detail is that Death is portrayed as a female figure - a kind of inverted Madonna and Child - instead of eternal life the figures represent the certainty of death as the final part of life. The use of a female motherly figure could also suggest the dangers of childbirth at the times - as well as being a giver of life, the mother can also bring death upon the child. The composition of this painting is intriguing - the viewer is looking in between the wings of Death, the light source is uncertain and the background is dark; all the viewer's attention is focused on the two figures.

Field of the Slain 1916 Evelyn De Morgan

. L'Angelo Della Morte (The Angel of Death) 1896

The Angel of Death 1881 Evelyn De Morgan

This painting by Evelyn De Morgan depicts the Angel of Death. The gender of the figure is ambiguous and it seems almost a gentle being - Death is not an unwanted presence, but a thing to be embraced. The composition of the painting is very effective - the posture of the two figures echo each other, and it is very flat in composition, like a Renaissance painting, drawing the viewer's eye to the figures in the centre. The cypress trees in the background are symbols of death - in Ancient Greek and Roman times the cypress was known as 'the mourning tree' and it was linked with the Gods of the Underworld, Fate and the Furies. The cypress is also though of as a symbol of hope - for the trees are pointing towards heaven.

Field of the Slain 1916 Evelyn De Morgan

In this painting De Morgan depicts the Angel of Death as female, lending a rather motherly, caring quality to a figure that is usually morbid and sinister. Given the date and the title, this painting could be taken as De Morgan's response to the horrors of the First World War.

Twilight, Pity and Death 1889 Simeon Solomon

Death features a lot in many of Simeon Solomon's works. The above watercolour shows personifications of Twilight, head lifted to the sky; Pity, a flame burning above the head; and Death, eyes closed and clad in armor. The depiction of Death is an interesting one; it is one of the most discernibly male figures in Solomon's work - most of his figures are decidedly androgynous and ambiguous. Below are some other of Solomon's drawings which feature Death.

. L'Angelo Della Morte (The Angel of Death) 1896

Death Awakening Sleep 1896

Sin Gazing Upon Eternal Death

Sleep At The Antichamber Of Death 1896

.jpg)

.jpg)