Beautiful and elaborate hairstyles are often associated with the Victorian Era, but it is often overlooked how the ladies actually managed to achieve these fantastic creations. During the 19th century the hairstyles changed to compliment the ever-changing fashions of dress. With the 1870's came the bustle period, and consequently hairstyles became increasingly elaborate, with a preference for long tresses, masses of hair piled on the head, adorned with flowers, combs and ribbons.

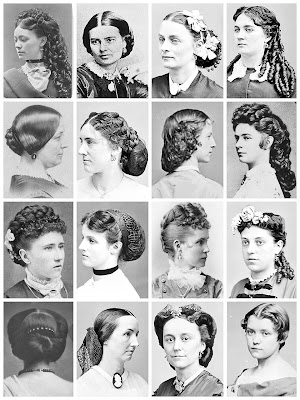

A few examples of 1870's Hairstyles

With the invention of the curling tongs in 1866, it was now even easier for women to achieve the thick curls they desired for their hair. However, this new invention lead had many problems - frequent use of the curling tongs left ladies hair matted and burned; much the consistency of wool or felt, and rather smelly. To achieve the massive hairdos so desired, much false hair was needed. It was extremely common for Victorian women to keep the hair from their hairbrushes to use as padding, or 'rats' as they we called, for their hairstyles, but it was not desirable to have 'rats' showing through, nor was it a sufficient amount to create the tall and elaborate hairstyles.

A selection of Victorian photographs, to show the variety of hairstyles through the era.

Even by the 1880s, false hair was still very much in demand. Though false hair was no longer needed for much of the Victorian women's hairstyles of the period, it was still wanted to make fringes. Fringes, or bangs, became extremely popular in the late 1870s and early 80s, through Queen Alexandra, who was famous for her rather massive curly fringe. Because many women did not like to cut the front of their hair, and liked to keep it long, false fringes were often worn to fit in with the fashion. The false hair industry was subsequently huge in the Victorian western world, especially in Paris and London. Here is an extract on the London human hair market from Victorian social journalist John Greenwood, from his 'In Strange Company' of 1874. It is a rather long extract but thoroughly enjoyable to read, for Greenwood, being the great journalist he is, writes with such fluency and description.

Even by the 1880s, false hair was still very much in demand. Though false hair was no longer needed for much of the Victorian women's hairstyles of the period, it was still wanted to make fringes. Fringes, or bangs, became extremely popular in the late 1870s and early 80s, through Queen Alexandra, who was famous for her rather massive curly fringe. Because many women did not like to cut the front of their hair, and liked to keep it long, false fringes were often worn to fit in with the fashion. The false hair industry was subsequently huge in the Victorian western world, especially in Paris and London. Here is an extract on the London human hair market from Victorian social journalist John Greenwood, from his 'In Strange Company' of 1874. It is a rather long extract but thoroughly enjoyable to read, for Greenwood, being the great journalist he is, writes with such fluency and description.

IT was recently my privilege to inspect, and for just as long as I chose, linger over the enormous stock of the most extensive dealer in human hair in Europe. The firm in question has several warehouses, but this was the London warehouse, with cranes for lowering and hauling up heavy bales. I, however, was not fortunate in the selection of a time for my visit. The stock was running low, and a trifling consignment of seventeen hundredweight or so was at that moment lying at the docks till a waggon could be sent to fetch it away. But what remained of the impoverished stock was enough to inspire me with wonder and awe. On a sort of bench, four or five feet in width, and extending the whole length of the warehouse front, what looked like horse tails were heaped in scores and hundreds ; in the rear of this was another bench, similarly laden ; all round about were racks thickly festooned ; under the great bench were bales, some of them large almost as trusses of hay; and there was the warehouseman, with his sturdy bare arms, hauling out big handfuls of the tightly-packed tails, and roughly sorting them.

I should imagine that a greater number of pretty lines have been written on women's hair than on anything else in creation. Lovers have lost their wits in its enchanting tangle; poets have soared on a single lovely tress higher than Mother Shipton ever mounted on her celebrated broom; but I question if the most delirious of the whole hair-brained fraternity could have grown rapturous, or even commonly sentimental, over one of these bales when, with his knife, the warehouseman ripped open the canvas and revealed what was within. Splendid specimens, every one of the tails. Eighteen or twenty inch lengths, soft and silky in texture, and many of rare shades of colour-chestnut, auburn, flaxen, golden - and each exactly as when the cruel shears had cropped it from the female head.

It was this last-mentioned terribly palpable fact that spoilt the romance. Phew! One hears of the objectionable matters from which certain exquisite perfumes are distilled ; but they must be roses and lilies compared with this raw material out of which are manufactured the magnificent head-adornments that ladies delight in. As to its appearance, I will merely remark that it, gave one the "creeps" to contemplate it. Misinterpreting my emotion, the good-natured gentleman who accompanied me hastened to explain that the fair maidens of Southern Germany to whom these crowning glories had originally belonged did not part with the whole of their crop. "More often than not," said he, "they will agree to sell but a piece out of the centre of their back hair, and under any circumstances they will not permit the merchant's scissors to touch their front hair." Time was when I should have derived consolation from this bit of information; but now I could not avoid the reflection what a pity it was, for sanitary reasons, that they did not have their heads shaved outright. "Is it all in this condition when you first receive it?" I ventured to inquire. "As nearly as possible," was my friend's bland rejoinder.

The lot under inspection, a little parcel of a couple of hundredweight, came from Germany. The human hair business has been brisker in that part of Europe than anywhere during the past few years, on account of its yielding a greater abundance of the fashionable colour, which is yellow. Prices have gone up amongst the "growers" in consequence. The average value of a "head" is about three shillings. As well as I can understand the matter, however, the traffic in human hair is based on pretty much the same business principles as those which find favour with the "old clo'" fraternity with which we arc familiar. With them articles of' china and glass are exchanged for an old coat or a brace of cast-off shoes - a pair of Brummagem earrings, a yard or two of flowered chintz, or a pair of shoe-buckles are offered for a cut out of the back hair of the German peasant maiden. The hair buyers - or "cutters," as they are technically called - are pedlars as well, and never pay for a shearing with ready cash when they can barter. These pedlars are not the exporters, however ; they are in the employ of the wholesale dealer, who entrusts them with money and goods, and allows them a commission on the harvest. I don't think that I was sorry to hear about the Brummagem earrings and the barter system. Since civilisation demands the hair off the heads of women, it is consolatory to find that they think no more of parting with it than with a few yards of lace they have been weaving. It comes from Italy as well as from Germany, and recently from Roumania. I was informed that an attempt has been made to open a trade with Japan but, though the Japanese damsels are not unwilling, at a price, to be shorn for the adornment of the white barbarian, the crop, although of admirable length, is found to be too much like horsehair for the delicate purposes to which human hair is applied.

Brown hair, black hair, hair of the colour of rich Cheshire cheese, hair of every colour under the sun, was tumbled in heaps on the counters before me, including grey hair - notmuch of it, as much, perhaps, as might be stuffed into a hat-box; but there it was, the hair of grandmothers. Seeing it to be set aside from the rest, my impression was that it got there through one of those tricks of trade that every branch of commerce is subject to. That lot was stuffed into the middle of a bale, I thought, by some dishonest packer who, while aware how valueless it was, knew it would help to make weight.

"You don't care much about that article I imagine," I remarked to my guide.

"What! that grey hair-not care for it!" he returned, with a pitying smile at my ignorance. "I wish that we could get a great deal more of it, sir; it is one of the most valuable articles that comes into our hands. Elderly ladies will have chignons as well as the young ones; and a chignon must match the hair, whatever may be its colour." It was unreasonable, perhaps; but, for the first time in my life, as I gazed on the venerable pile, I felt ashamed of grey hair. It seemed so monstrously out of place.

But I had yet to be introduced to the strangest branch of this very peculiar business. I had inspected packs, heaps, and bales of human tresses of every length, colour, and texture; but every hair of it had been shorn, living and vibrating, from the human head. Now, I was invited to look at a lot of "dead hair," in a bale which would make a Covent Garden porter of only average strength shake at the knees before he had gone a hu'ndred yards.

"This is a very extraordinary kind of article," said my kind informant, as he ripped open the stout cloth covering; "this is the 'dead hair' you read of in newspapers and magazines."

Involuntarily I edged a little further from the gash in the canvas.

"But is it really dead hair-hair, that is to say, that has been -"

"Buried and dug up again," my friend blandly interrupted ; "not exactly, though that is the blundering popular impression. This, my good sir, is an article that is not cut from the head. It is torn out by the roots. It all comes from Italy."

"Torn out by the roots! What! violently!"

"Violently, my dear sir."

I trust that my look of incredulity had nothing of rudeness in it. I had heard of hair being torn out of the human head by the roots - nay, in more than one frightfully desperate case I had seen as much as a big handful produced before a police magistrate to prove the murderous antipathy of Miss Sullivan for Mrs Malony; but what was that small quantity compared with as much as might be weighed against a sack of coals? Could it be possible that the ladies of Italy were so terribly quarrelsome that --; but, observing my perplexity, my friend hastened to explain.

"Torn from the head with gentle violence. I should have said, and with weapons no more formidable than the brush and the comb. When I hold the head" - let the hair be living or dead, he called every separate hank of it a "head" - "to the light, you will see that every hair has its root attached, and all that you see here is only a small part of the bulk that finds its way every year to market. It is simply the hair that becomes detached from the heads of Italian women in the ordinary process of combing and brushing. As a married man, you may know what happens when a lady brushes her hair; she will pass a comb through the brush, give the detached waifs of hair a twist round her finger, and make a loop to it to keep it tidily together till it is thrown away. A like habit with Italian women is the mainspring of our English dead-hair supply. In the poor districts of Italy especially, the little twist of waste hair finds its way to the washing-basin, and so to the street gutter, out of which it is fished by the scavenger. From his hands it passes for the merest trifle into those of the knowing ones, who know how to disentangle the ugly little tufts, to arrange them as to length and colour, and send them to market as you here see them."

As I saw them, they differed little from the thousands of other "heads" piled on all sides, except that they were somewhat shorter. Indeed, they were cleaner-looking; but, after what I had heard about them, it was difficult to contemplate them without a shudder. They were worth a third less as a marketable article than "live hair," I was informed; but the supply was abundant, and many hundredweights were used in the course of a year. Many hundredweights; and about two ounces will make a respectable chignon! It is a dreadfully unpleasant fact, ladies, but so it is. To be sure, the perfect machinery used in the preparation of human hair before it finds its way into the hands of the hairdresser ensure its absolute cleanliness ; but it is not nice to reflect that at the present time hundreds of your lovely sex are crowned with Italian peasant women's brush-combings, consigned first to the slop-basin and then to the street- kennel, to be rescued therefrom by the rake of the scavenger.

No comments:

Post a Comment